Last month, GitClear published an analysis of 211 million lines of code in its AI Copilot Code Quality report. One of the key findings is that refactoring signals are crashing while code duplication and churn is increasing. In fact, 2024 is the first year when the introduction of repeated code is greater than refactoring activity.

The trend is attributed to the rise in AI coding assistants, and if it continues, we could be heading toward a software crisis.

The Race To Adopt AI

If you work in software development, someone has told you that “AI won’t replace developers; developers using AI will replace developers who don’t.” The message is clear: either use AI or you’re heading for a career change. More positive messages suggest we could remove toil work — the tasks that require high repetition and little thought.

The recent Stack Overflow State of Development survey found that more than 60% of developers are now using AI as part of their work, and more are planning to do so. The primary motivation for AI adoption is increased productivity. As the GitClear report shows, the dramatic downside of wanting to increase productivity is that you may wind up removing your bicycle chain in order to peddle faster.

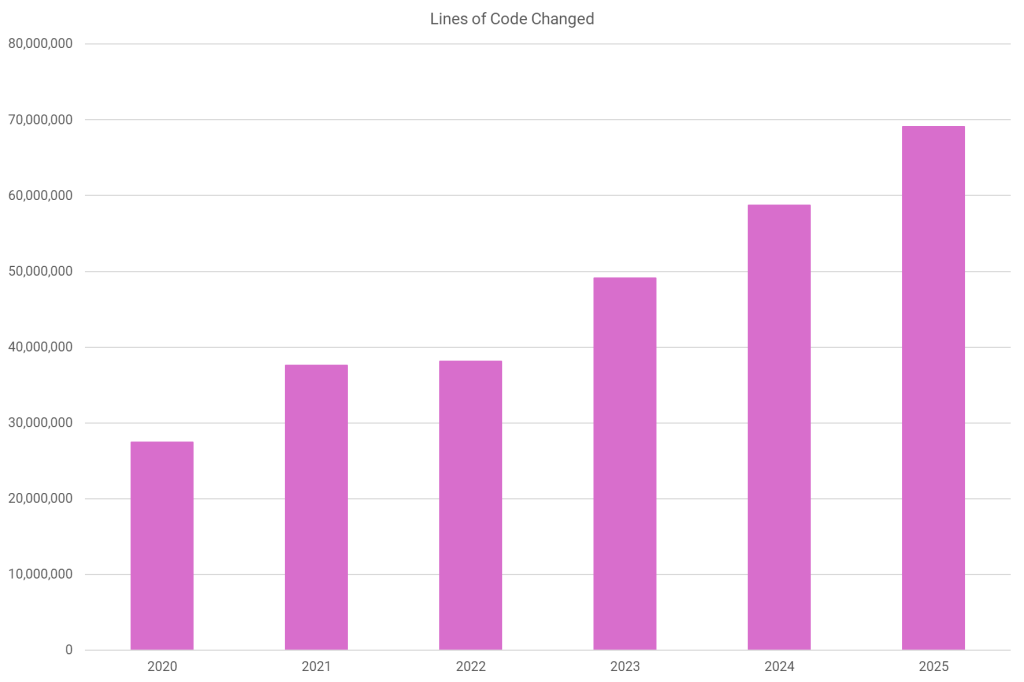

In the case of software development, we are now rapidly accelerating the rate of change in our codebases. In 2025, the rate of change is predicted to be almost double the pre-AI (2021) number.

The accelerating rate of change, including the predicted 2025 total. Image from Octopus Deploy. Data source: GitClear.

This leap in productivity is likely seen as great news by many, particularly those selling AI. However, we should remember the wisdom of our predecessors. Productivity provides a poor view of knowledge work and has been permanently elusive in its measurement.

“There is surely nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency what should not be done at all.” – Peter Drucker, 1963.

Throwing Out Good Practice

Before we became productivity-obsessed, there were some foundational practices that the software industry found to be highly valuable. One of these is refactoring. You build more reliable systems when you continuously revisit your code to keep components loosely coupled and to make sure you define concepts just once. You would keep things together if they changed for the same reason and tease them apart if they had different drivers for change.

My bookshelf creaks beneath the weight of software design literature by Kent Beck, Emily Bache, Martin Fowler, Robert C. Martin, Michael Feathers, Rebecca Parsons, Steve McConnell and more. These books contain lasting techniques and practices that are vital to successful software over the long haul. Coding assistants don’t change the fundamentals of software development.

If we accelerate the rate of change, we must match this by keeping pace with the software’s internal structure. In other words, for this to result in a successful long-term software development strategy, we must be able to refactor at the same pace we change the code.

But the report highlights that this is not currently the case.

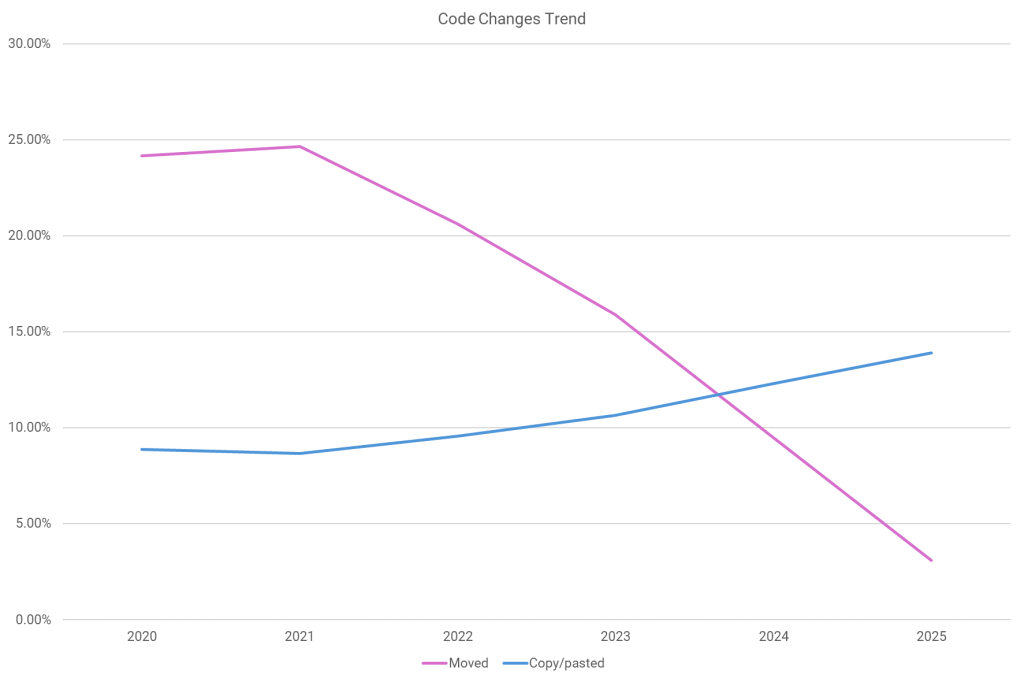

Refactoring activity is tracked using a category of change called “moved code.” This is where the fundamental logic remains the same but has been shuffled to improve the code’s design. This includes classic refactoring patterns like “extract method” or “rename variable,” which are typically automated by developer tools to guarantee they are safe refactorings (not to mention the practice of test-driven development should mean your tests would catch any accidental behavioral changes).

Since 2021, the proportion of refactoring changes has plummeted from 24% to below 10%. At the same time, the number of copy/pasted lines of code, or duplication, has increased from below 10% to almost 15%.

The dramatic loss of refactoring and the climb of duplication.

The prediction for 2025 is that we will reach a point where refactoring is dead, representing little more than 3% of code changes. Our software will continue for some time before the effects of this become clear.

The Lesson Comes Too Late

I’m reminded of an organization where I successfully replaced a chaotic, fragile process with continuous delivery. The key practices installed were test automation, deployment automation, and a solid monitoring and alerting system. The combination of these tools dramatically improved reliability, and elevated the levels of trust between developers and business stakeholders.

After I left, the team decided that managing test data was an undesirable task. They deleted the database script that ran on test environments to reset data to a known state. For many months, the integration tests still worked, and would have continued to work if nobody had manually changed the test data for the test record configured for integration testing.

Once the test data was spoiled, the team faced a tough choice. They could recreate the test data management script, updating it so it worked with all the database changes they had made. Alternatively, they could delete the failing tests. Under pressure to deliver features (and remain “productive”), the team deleted the tests.

Deleting tests has no immediate impact. The feature continued to work for some time, but errors were eventually introduced, and then became a recurring issue.

This is the problem that arises when you choose productivity over long-term sustainability. It takes a long time to realize there’s damage. When the impact of past decisions is apparent, it can often be too late to mitigate it.

Flying vs. Falling

AI code assistants provide the perfect conditions for parabolic software velocity. Just like the zero-gravity plane flights, which use a parabolic curve to provide a feeling of weightlessness, code assistants make us believe we’re flying when we’re actually following a ballistic trajectory in free fall.

For AI to sustainably increase your productivity, you can’t let it dictate your code quality.

The post What’s Missing With AI-Generated Code? Refactoring appeared first on The New Stack.