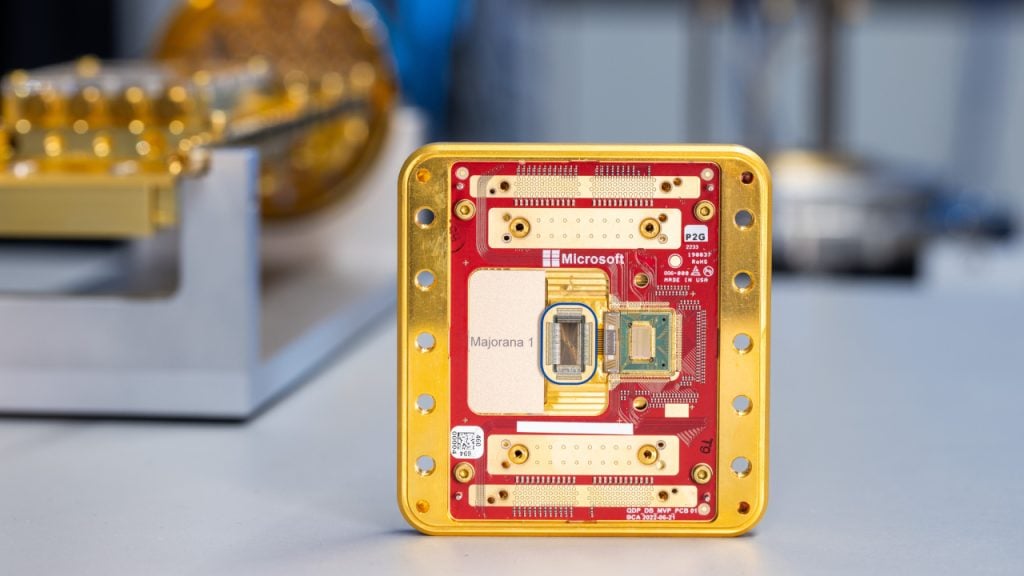

Microsoft’s new state of matter promises true quantum computing with a million qubits — maybe by 2033. The company is also announcing its own quantum chip, the Majorana 1, in a form factor that can scale up to a 1 million qubit Quantum Processing Unit, ready to attach to a dilution refrigerator and slot into an Azure data center.

The promise of quantum computing is being able to accurately model the laws of physics and the systems of the natural world. It could revolutionize medicine and material science. Even before we get into designing and simulating novel materials, designing enzymes to break down microplastics or creating more effective, less polluting fertilizer, we could get breakthroughs in batteries and power distribution by being able to simulate widely used materials — from magnets to superconductors — that we don’t understand well enough to use as efficiently as we could, as accurately as running an experiment in a physical lab.

Microsoft has taken a very different approach from most of its competitors, relying on exotic particles it had to prove even existed — let alone could be controlled.

Getting quantum computing to scale from the small-scale, experimental systems already available today to systems that deserve the name requires reliable qubits — qubits that don’t require so much error correction that it takes hundreds of physical qubits to create one logical, stable qubit that can perform a calculation with a readable result and that can be easily controlled.

Running a useful, real-world quantum computing application will involve a lot of computations, which means performing trillions of operations on a million qubits. Quantum computing hardware available today requires significant error correction and has to perform individual fine-tuned analog control of every individual qubit using precisely shaped control pulses for both running the system and correcting errors (with any deviation from that introducing more errors), which is hard to scale reliably to such large numbers.

Microsoft is far from the only company working on quantum computing, but it’s taken a very different approach from most of its competitors, relying on exotic particles it had to prove even existed — let alone could be controlled.

After hiring award-winning mathematicians and physicists in the late 1990s and funding multiple experimental physics labs around the world to find the particles they believed could power a reliable quantum computer, Microsoft convinced leading processor architects like Burton Smith, the cofounder of Cray and Pentium architect Doug Carmean to join its Station Q lab. Microsoft’s quantum team has spent the last two decades working out how to use these one-imaginary particles to build topological qubits that are smaller and more stable and that need less power. They also have less error correction and are said to be much easier to control, so you can build enough of them into a quantum computer to be useful.

Making Majorana Matter Real

The Majorana particles Microsoft has pinned its hopes on — which hide quantum information, protecting it from random interference but also making it harder to measure — are so exotic that although they were predicted in 1937 (by the extraordinary but reclusive physicist, they’re named for), until recently, they’d never been reliably detected. They’re the simplest type of a different kind of matter called a non-Abelian anyon: particles named because they seem to be capable of almost anything, including sharing the “memory” of whether they have crossed paths with another anyon before or not, a memory that can be used to store and manipulate information.

Bring two anyons together and they might destroy each other and collapse into a vacuum — or they might become an electron. That kind of superposition (existing in multiple states at once because you don’t know which outcome will happen) is how quantum computers can explore a vast number of solutions at once.

Swap the position of two anyons by moving them around each other and they switch their quantum state; bring them together and the way their quantum state shows whether or not they’ve crossed paths before acts as a memory you can read.

Microsoft is announcing the Majorana 1 quantum chip, initially with eight topological qubits and connectors to interact with it.

Moving the trajectories of pairs of Majoranas around is called braiding (the different twists and turns of the braid are its topology). This stops the information from being read until the computation is complete; because while they’re moving, it’s stored in all the Majoranas rather than in a single place that can be easily (or accidentally) read — which would cause the quantum state to decohere before you want it to. That means topological qubits should be both less error-prone and more stable than the alternatives.

But Majoranas — and this new, topological state of matter they represent — don’t happen naturally. They’re made out of electrons and have to be created at very low temperatures using magnetic fields and superconducting materials. Now Microsoft is showing peer-reviewed results in a Nature paper that prove researchers are really seeing and controlling the exotic quantum properties you need to create a topological qubit (and not a more prosaic quantum state that doesn’t deliver the reliable qubits that can scale to the massive numbers of qubits required for real quantum computing).

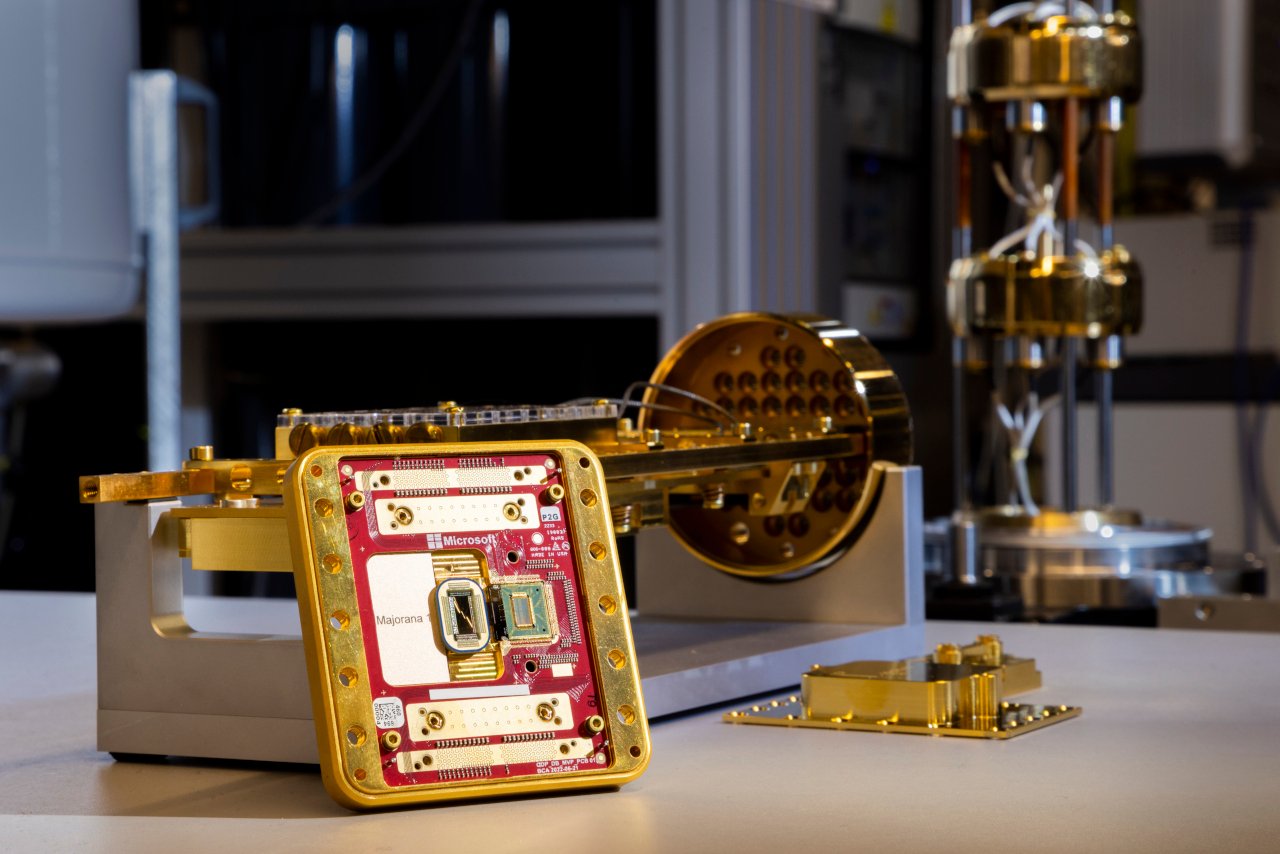

Microsoft is also announcing its own quantum chip, the Majorana 1. It will initially have eight topological qubits and the connectors to interact with it, but in a form factor that can scale up to a 1 million-qubit Quantum Processing Unit. It will be ready to attach to a dilution refrigerator and slot into an Azure data centre.

Microsoft’s Majorana 1 chip puts eight tiny qubits into a processor you can hold in your hand but it needs to attach to a very large refrigeration unit.

Error Resistance, Not Error Correction

Explaining quantum phenomena often sounds almost poetical: in 2019, Dr. Kyrsta Svore, head of the Microsoft Research quantum architecture group, described topological qubits as more like Incan quipu than chalk marks on rock, which will disappear in the rain: even in a storm, knots in rope won’t get untied. “Our computations are braids in space-time,” she said.

In 2016, Peter Lee, head of Microsoft Research, compared the more common supercomputing qubits to laying out thousands of tops in a gym, all spinning at once, some going in one direction and others the other way. “For superconducting qubits, we have the engineering knowledge to do that.”

The electrons that conduct electricity through a superconductor travel in pairs: they turn into quasiparticles called Cooper pairs, with the two electrons acting like a single particle and sharing the same quantum state. That’s what makes a material superconducting because the paired electrons move without resistance. If there’s an odd number of electrons, one of them won’t be in a pair, so it needs more energy to move. The energy difference between having an odd and even number of electrons is something you can measure and use to represent 0s and 1s (or ground state and excited state).

Topological superconductors – which Microsoft calls topoconductors – have all the same properties as normal superconductors.

The problem is that the spinning tops aren’t very stable, and neither are the superconducting qubits. They decohere quickly and are very vulnerable to interference from the environment (like heat, stray subatomic particles or magnetic fields) that breaks the Cooper pairs apart and collapses the quantum state of the electrons, causing errors.

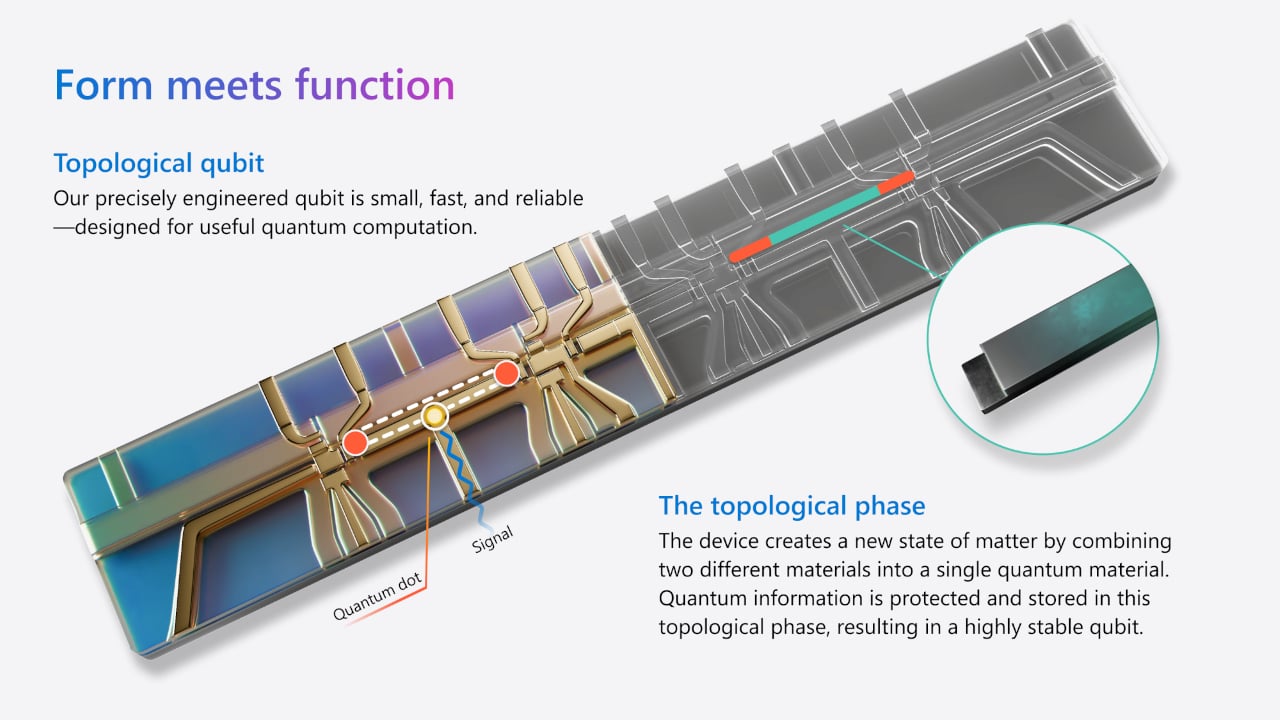

Topological superconductors — which Microsoft calls topoconductors and makes by combining indium arsenide, a semiconductor, and aluminum — have all the same properties as normal superconductors. But they also “hide” the unpaired electron using braiding: that means it’s much less likely to be affected by any interference, making the qubit inherently more stable but also harder to read.

Typically, designing qubits is about making trade-offs: making a qubit more stable with lower error rates usually means making it larger, slower or harder to control. Microsoft’s topological qubits are robust, but they’re also small and fast — and the team worked out a technique that makes them easier to both control and read.

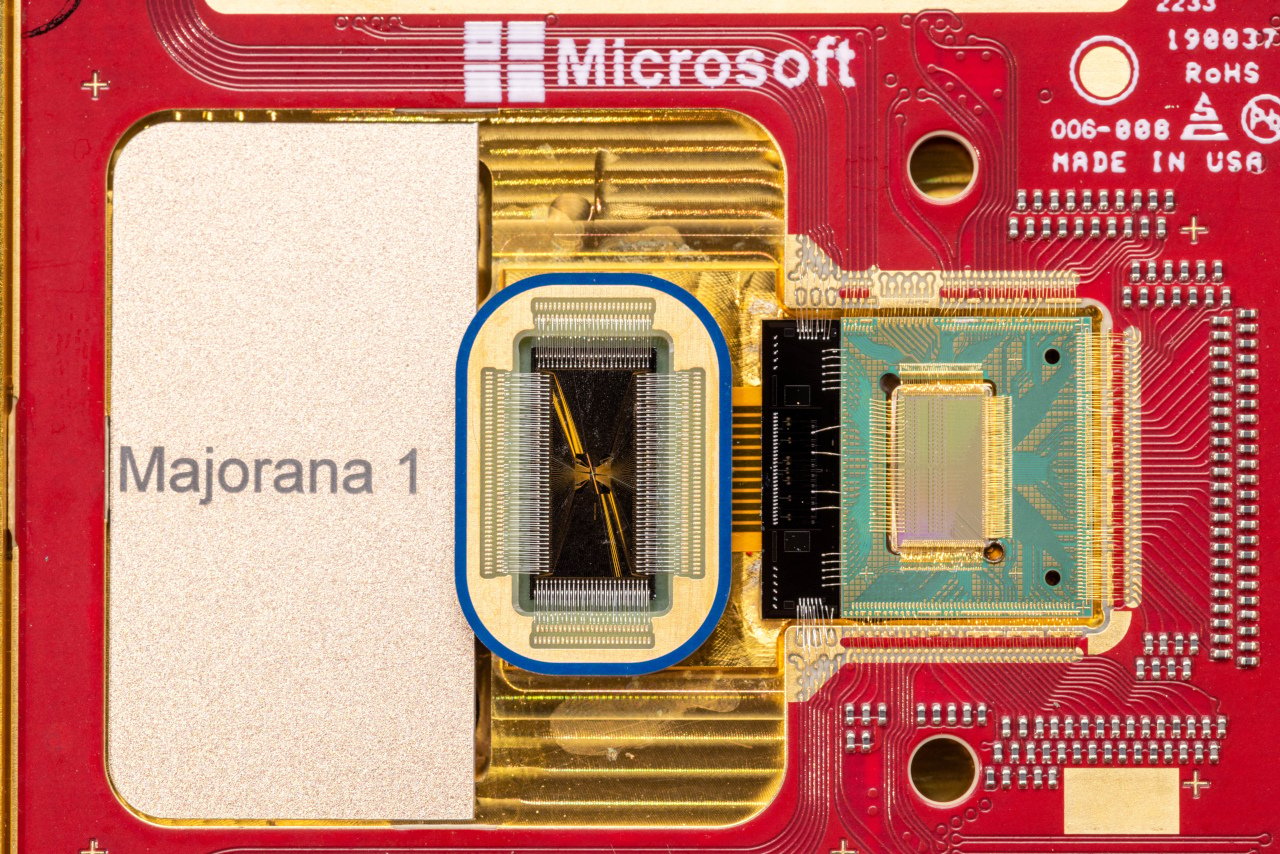

Each topological qubit is an H shape made by connecting the middles of two longer topological nanowires with a shorter superconducting nanowire (just one micrometer long). Microsoft calls that a tetron because there are four controllable Majoranas (one at either end of the topological wires — so they’re less likely to all be affected by the same interference).

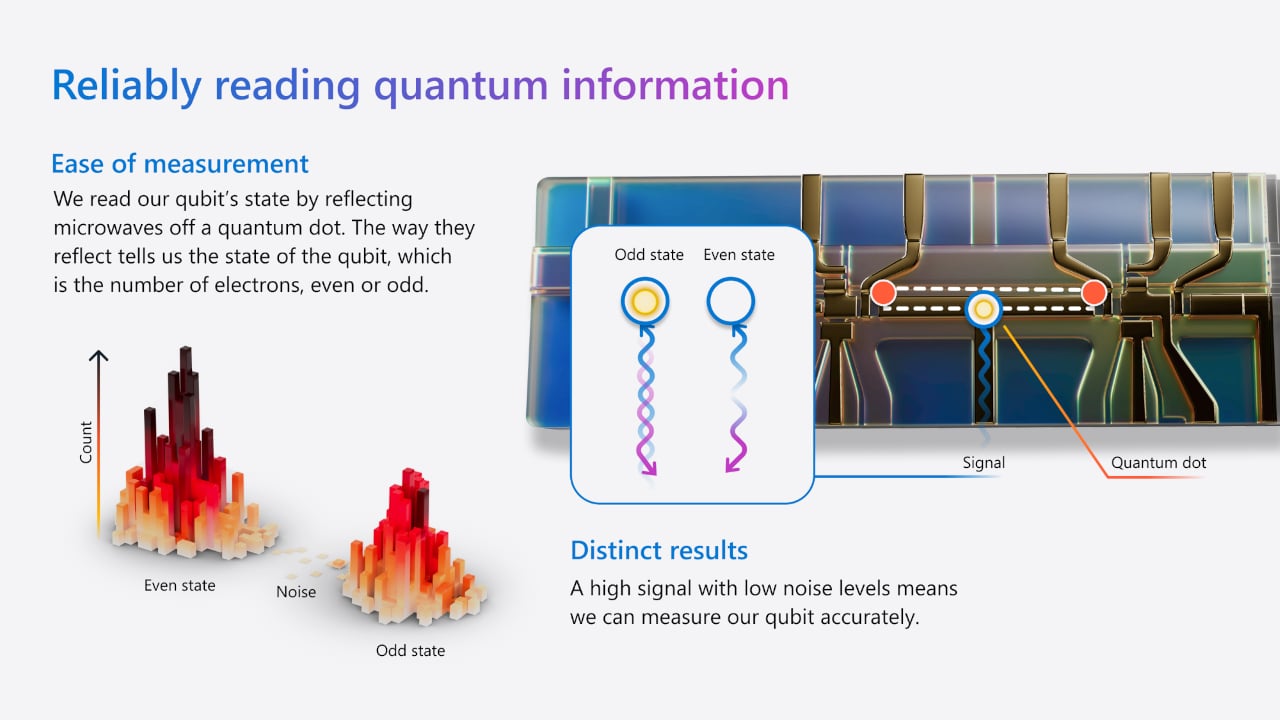

Each end of a topological nanowire is connected to a quantum dot — a tiny capacitor that can hold a charge as small as a single electron. The connection increases how much charge the quantum dot can hold and that’s different depending on whether there’s an odd or even number of electrons in the nanowire. The quantum dot reflects microwaves differently, depending on how much charge it can store — making it easy to read the quantum state of the nanowire.

“Our computations are braids in space time.”

– Dr Kyrsta Svore, head of Microsoft Research quantum architecture group

Send the charge from the quantum dot along the nanowire and it goes in through one Majorana and out through the Majorana at the other end, swapping their positions and looking at both of them to get the information by effectively counting the number of electrons in the wire. You can even measure across multiple wires at once — and the measuring has the same braiding effect as physically moving the Majoranas around.

The measurements are both fast and accurate: precise enough to detect whether a superconducting wire contains a billion electrons, or a billion and one. Knowing whether that number is even or odd tells the computer what state the qubit is in (like a 0 or 1 in the binary used by classical computing), so that you can use it for quantum computation. Reflecting microwaves off the quantum dot gives a clear signal with so little noise that you can be certain the measurement is correct.

The system Microsoft developed for taking those measurements is also the same way it controls the qubits. Disconnecting one quantum dot and connecting a different dot to both nanowires brings the Majoranas together, creating the superposition. It still uses pulses of voltage the way conventional qubits do, but it doesn’t require those control pulses to be as precisely shaped and timed — they just have to get the qubit to somewhere near the optimal point for taking a measurement, so the control system is more robust.

A simple digital pulse connects and disconnects the quantum dots from the nanowires, like pressing a light switch on or off rather than turning a dial to a specific setting. It doesn’t matter if you tap the light switch slowly and gently, or quickly and hard, as long as you move it to the right position. That should also mean the control system is easier to design and cheaper to build because it doesn’t have to be as precise.

The H shape also makes these qubits easier to interconnect: the ends of the H’s can be connected to each other to create a chip with many qubits. One way of making qubits more stable is to make them larger; you don’t have to make that tradeoff with topological qubits. These are just three by five micrometers (much smaller than many other qubits), so there’s room for millions of them on a single wafer. A chip the size of a watch face (or, say, a classic Pentium) will be able to fit a million qubits — but you won’t be putting them into a laptop.

Quantum Clouds

Cloud computing is an obvious match for quantum computing. It’s not just the cost — few organizations have the resources to install the specialized infrastructure required for quantum hardware, starting with a hefty concrete pad for stability and the dilution refrigerators required to deliver temperatures below 1 Kelvin (that’s about -272°C or -457°F, much colder than outer space). Quantum hardware needs extremely low temperatures both for the superconducting materials used in the qubits (it’s the superconductors that make quantum effects strong enough to be observed and used for computation), and to reduce the sensitivity of qubits to their environment. Keeping them extremely cold helps maintain their quantum state long enough to do complex calculations without decohering.

As quantum computers become more powerful, you’ll be able to mix classical and quantum compute.

As well as a very stable and cold environment, you also need petascale classical computing with 100Tbps connections to read the information from the quantum computer every cycle. As quantum computers become more powerful, you’ll be able to mix classical and quantum compute, using the classical computers not just to prepare data for and process the output from the quantum computer between jobs or even in real-time, but for hybrid quantum computing where some of your algorithms run in classical code (and can be more complex than just loops to send and receive data) while the quantum system handles optimization and simulation problems.

While it’s been working on its own quantum computing hardware, Microsoft has also been building out a quantum computing stack, with its Q# development language and quantum algorithms that can run on the quantum hardware from IonQ, Pasqal, Quantinuum, QCI, and Rigetti that’s available through Azure — but the most powerful systems so far are still in the 20-30 qubit range.

Using Atom Computing’s neutral-atom system (which cools, arranges and excites atoms of alkali metals like rubidium so they interact, then photographs how fluorescent they are to get the result of the computation), Microsoft created and entangled 24 logical qubits from 112 physical qubits. It also made four logical qubits (that it describes as “highly reliable”) from 30 of the 32 trapped ion qubits (controlled using lasers) in Quantinuum’s H2 quantum computer (also available through Azure Quantum).

A prototype fault-tolerant quantum computer will be available “in years not decades.”

– Chetan Nayak, Microsoft’s VP of quantum hardware

In 2003, researchers at Harvard used 27 of the H2’s qubits to create and braid three pairs of non-Abelian anyons inside the qubits. That was more proof of the underlying physics, but while the researchers had to go through multiple stages of selective measurements designed to deliberately decohere quantum states to create a topological phase of matter (think of it like a virtual qubit), Microsoft’s qubits will create Majoranas directly — and then use them for computation.

Microsoft vs. Google

A prototype fault-tolerant quantum computer will be available “in years, not decades,” promised Chetan Nayak, Microsoft’s VP of quantum hardware.

The potential of topological qubits is why DARPA announced earlier this month that Microsoft is one the first two companies to be invited to join its rigorous program for investigating whether it’s possible to build a useful quantum computer — where the value of the computing it can do is worth more than what it costs to build and run — by 2033, using what the agency calls underexplored systems. (The other company, PsiQuantum, is taking its own completely different approach using silicon-based photonics, with lasers connecting the qubits.)

That’s a similar timeline to the 5-10 years Google CEO Sundar Pichai recently predicted until we get “practically useful” quantum computing. At the end of 2024, Google demonstrated quantum error correction (QEC) that gets better rather than worse when using more physical qubits to create a logical qubit on its Willow chip (that has 105 physical qubits but only 49 logical qubits).

Unlike Microsoft’s topological qubits, which use topological space, Google is using more traditional superconducting qubits.

Unlike Microsoft’s topological qubits, which use topological space to protect the information in the quantum state from outside interference for long periods of time, Google is using an array of more traditional superconducting qubits. Google uses the oscillation of Cooper pairs of electrons across Josephson junctions — two superconductors that are placed close together but with a thin insulating barrier between them.

Some of Google’s qubits store the data for the computation. But because superconducting qubits are so prone to errors, they’re surrounded and separated by other qubits that are only there to measure the data qubits to see if there are errors. Google’s quantum chip spends a lot of its time running sophisticated quantum error correction (QEC) techniques (called surface codes) to maintain the correct quantum state in the data qubits.

Google is working with a qubit design that’s been widely used and studied. It’s powerful — in 2022, researchers working with Google actually simulated an extremely simple example of topological braiding using defects in the qubit — but it’s relying on its expertise in software to compensate for the inherent problems of that design.

Microsoft has taken a much riskier approach that has major theoretical advantages.

By spending 20 years working on topological qubits, Microsoft has taken a much riskier approach that has major theoretical advantages but was completely unproven when it started. Also, it required doing some fundamental work in physics in conjunction with university research departments, in addition to developing the manufacturing and measurement techniques required to build its qubits and (like Google) creating the labs and facilities to build their qubits.

After a misstep in 2018, when a research paper based on an over-optimistic interpretation of incomplete data had to be retracted, Microsoft has been extremely cautious about announcing its progress on topological qubits, working with external researchers and independent experts to check and double-check its progress. It’s now reached the stage of not just building its first topological qubits but delivering measurements that show how they shape up — and how Microsoft can use them to deliver quantum computing at scale.

Quite Easily Corrected

Initially, there are just eight physical qubits in the Majorana 1 QPU, which Microsoft can assign in different ways to get the number of logical qubits it wants. Calling it a QPU is a reminder that there will probably be a lot of different kinds of quantum computer, and that researchers will pick the one that suits them — like choosing a different GPU for a specific workload.

First, Microsoft will use two qubits on Majorana 1 to show it can do the entanglement and braiding promised in its quantum roadmap. Then, it will use all eight qubits as two logical qubits with quantum error correction (although using very different algorithms from Google, which it says are ten times as efficient, run faster and need fewer physical qubits).

The first topological qubits are probably more like vacuum tubes than transistors […] there’s a lot more work to be done.

It’s not that Microsoft’s topological qubits don’t need any error correction; although errors are much less common because the quantum state is “hidden” and thus protected, they can still occur. For one thing, having QEC is one way to reuse qubits that deliver a result partway through a computation; you just reset them to use for another computation, which means you don’t need as many total qubits. But because of the way the tetrons are built, they don’t need extra circuitry or spare qubits to do the error correction: they will just use the same quantum dot control and measurement system to apply quantum error correction or a qubit reset — another significant simplification of the design.

Nayak described the first topological qubit as a turning point: “It’s not the end of the journey by any means, but it’s really opening up a new vista.”

Because of the precision with which the materials have to be handled to create topological qubits and the topoconductor that powers them (they’re assembled with atomic precision in a vacuum), the team spent a lot of time building simulations of the topoconductor material; something that would have been a lot easier with a quantum computer.

The first topological qubits are probably more like vacuum tubes than transistors (let alone integrated circuits) when it comes to building quantum systems: there’s a lot more work to be done. But along with all the other potential breakthroughs we might see with quantum computing, it’s going to be easier to design new materials or at least make it easier to handle the materials we’ll need to build more powerful quantum computers.

The post Microsoft Makes Quantum Computing Breakthrough With New Chip appeared first on The New Stack.

Comments are closed.