“You’re not going to be replaced by a tool or by an AI. You’re going to be replaced by a person using AI.”

As the senior vice president of digital and ecommerce at Adidas, Fernando Cornago has learned that you can’t wait for a technology to be proven before you go for it. After all, like most brick-and-mortars, the top sneaker brand was devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We don’t know where our consumers will buy from us in a couple months,” Cornago reflected at the Enterprise Tech Leadership Summit. But he’s sure technology will be an essential part of that solution, just like it was to get Adidas back on track over the last four years. Today, digital sales make up over 20% of revenue, supported by half the staff.

From a cloud and microservices migration to a platform engineering strategy to now generative AI, Cornago’s team makes sure that Adidas is always an early adopter — so business speed, processes and technology aren’t left behind. At ETLS, both last September and this February, Cornago revealed how Adidas’s commitment to measurable DevOps transformation and experimentation allowed them to pilot generative AI with 500 engineers and beyond.

Success Is Measured in Revenue Impact

Back in 2021, Adidas had 1,400 engineers working on the online shop. During that tough time for global retail, the German sportswear company decided to cut almost all external consultancies, halving its engineering team in an effort of focus on nurturing in-house development staff.

Now that retail is back, the digital distributors are still growing 10% year over year, with $5 billion out of $24 billion revenue last year via online sales, across more than 80 countries, serving a billion consumers a year. On about half the staff, they are moving faster with 4,000 releases a year, five times faster idea to value.

Reliability is up too, with 99% release success. As previously covered on The New Stack, at Adidas, stability is defined as:

- Mean time to detect (MTTD).

- Mean time to recover (MTTR).

- Revenue impact.

Therefore, instead of measuring downtime, engineering measures business lost per second, with only 0.18% net sales lost due to system outage in 2024.

Cornago even offered a better representation of industry favorite term 10x engineering, saying “In our new architecture, every 10% growth in sales will only create 1% to 2% growth in software and ops running cost, so we are built for the future.”

6 Engineering Lessons From Adidas

Cornago offered six lessons that feed into this measurable success and are driving the next stages of digital innovation at Adidas.

1. Speed to Pivot.

“We need our technology to scale both regionally and [for] special moments,” he said. “We are consumer facing so we need to stay fast.”

Adidas was one of the first companies to connect to the TikTok API in China, which soon accounted for 30% of that market’s revenue.

2. Channels Open Doors.

The Adidas engineering strategy emphasizes a composable architecture that allows for a connected ecosystem that leverages many channels, without having to reinvent the wheel. While TikTok was a very successful channel in China, it wasn’t at all in Europe. However, by reusing components to experiment in new markets, less engineering time wasted in testing out new channels.

In fact, the company has cut 27% of its software costs since 2020, while quadrupling its release rate.

“I don’t want to talk about efficiency with our engineers,” Cornago said. “I want to talk about maximizing build value over running costs.”

This strategy will also enable Adidas to take the next step to make the ecosystem smarter, he continued, because it’s impossible to connect with a billion consumers manually. Composable architecture is also integral to the company to target and personalize via data and AI.

3. Platform as a Foundation.

Adidas is organized into platform domains, including infrastructure, data, and the platform engineering team itself. It is also early adopters of platform as product mindset as well as a product as a platform mindset, where data is treated as a product. With this in mind, golden paths are laid out in a way to enable speed for most teams, in a way that remains optional.

4. Value Stream Optimization.

Cornago described his engineering organization as “obsessed with maximizing value” — with over six years dedicated to value stream optimization, along the steps of the consumer journey.

“It was the easier way of getting clear business KPIs of how we bring the consumers into the platform, turning them into members, how to align them — with content, product, what they want — how we [process] the purchases, how we deliver the products, and how we give them the best customer service,” he said.

The last year has been about value stream optimization from the executive level on down, including flow distribution for the capacity allocation. He explained, “Cutting the team by half is forcing you to make choices and you don’t want to cut by too much on some topics like data privacy.”

How do they measure flow? After so many tools, he said, they went back to the basics — measure the time that a task takes for each of the steps. And ask managers to share three goals each quarter, based on the data.

5. Visualize Architecture.

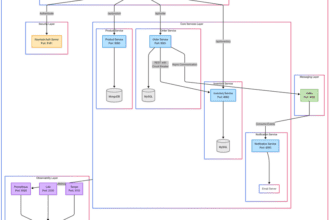

As most enterprises face, Adidas struggled to map out the sprawl of its more than 300 microservices, in order to enable those channel-first, plug-and-play capabilities for different markets.

In a mix of Wardley Mapping and an internal developer portal, Cornago’s team developed “a common language with business” for visualization, which they call the Capability Diamond. This practice has engineering catalog every reusable component it has. His team then combines these components into packaged business capabilities that come with APIs and event streams, behind an optional user interface.

6. Embrace Change.

Adidas was an early adopter of generative AI, just like it was of platform engineering and DevOps before that. In order to prepare for the next big technological shift, that demands, Cornago said, a culture that embraces experimentation and change.

The 500-Engineer GenAI Pilot

“In Adidas, it’s changing everything,” Cornago said, of generative AI. “Across customer service, support, content, and of course engineering.”

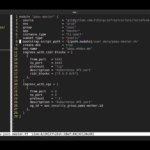

In Q1 2024, Adidas rolled out a pilot of the GitHub Copilot AI coding assistant across 500 engineers. Even in a relatively short trial period of three months, the impact on engineering effectiveness was clear.

When Copilot was available:

- 65% of engineers completed repetitive tasks faster.

- 61% completed any task faster.

As with all developer productivity initiatives, adoption rate is an essential measurement:

- 82% used Copilot for everyday coding work with familiar languages.

- 59% used Copilot to create repetitive code with familiar languages.

- 62% used Copilot to write tests with familiar languages.

A whopping 91% of developers in Adidas’s Copilot pilot responded that they found it useful and didn’t want to work without it, with:

- 79% using Copilot to create new code.

- 62% using it to change existing code.

- 61% finding it useful when documenting code.

“They really reported consistently between 20 and 25% more efficiency in their craft,” Cornago said. “They were faster achieving what they wanted to do, whether there was a change in their code, a creation of a new routine, a new algorithm or a new feature.”

Overall, about two-thirds of participants created more pull requests with Copilot than in the previous quarter without. This ended up translating to engineers reporting an overall improvement of 15 to 20% in their time coding and testing.

“There is no way that you can push a tool on our engineers,” Cornago said. “They will find a way not to use it and it will never pay off.”

And he is by no means making an argument that all GenAI is a panacea. Without revealing which GenAI tool they tried before Copilot, he did describe it as a disaster with 90% of developers responding that they were wasting their time firefighting and troubleshooting.

Still, Six months after the initial pilot, about 700 Adidas developers — around 85% of the engineering organization — are now using GitHub Copilot every day.

Value Time vs. Waste Time

No matter which report you read, it’s typical that developers spend less than 30% of their time coding and testing, which accounts for why the GenAI wins only accounted for about moderate overall productivity gains (even if the gains for coding were notable).

Any generative AI developer productivity strategy must examine more than just those activities. It must consider discovery, analysis, documentation and other important aspects of the developer lifecycle. Adidas dubs the time spent coding and testing Time in IDE. Unlike the McKinsey Developer Productivity Framework, which only focuses on coding and testing as priorities, Adidas is looking to measure the developer experience as Time on Keyboard, which encompasses both Time in IDE and those other activities. Time on Keyboard, Cornago clarified, does not include team ceremonies, meetings and trainings.

Adidas spent a month tracking the “Time on Keyboard” or “value time” of seven teams of 10 engineers each across four different domains, maturity and technology stacks.

“It’s not only coding, it’s also analysis, design, documentation. It’s all the jobs that the developers or the engineers are hired for. It’s what they love. When they thrive, it’s what they’re doing,” Cornago said, further defining Time on Keyboard.

“The rest is troubleshooting, dealing with misalignments with the business, discussing roles and responsibilities, trying to find the root cause of a problem between different documentations and asking access for a system. All this waste — ‘Annoying Time’.”

Adidas discovered it had a coding and testing time that knocks other industry benchmarks out of the park at 36% of developer time. To which he responded, “I still think it’s too low. I’m not quite happy with the results.”

However, as Adidas’s Time on Keyboard had shifted from 47% in 2018 to 65% of the time in 2024, Cornago said, “This is the number that makes me more proud.”

Not All Teams Can Be So Productive

When this examination of developer productivity was broken down, there was a clear discrepancy between what Cornago called high-performing, productive teams — that spend more than 80% of their day-to-day on “value” time — and the rest, which had less than half.

“The correlation is very clear with the seniority of the team, with how mature is the DevOps journey, and with how loosely coupled and open the technologies they use,” he said. According to the company’s quarterly survey, the high performing teams also feel more connected with the company vision. With generative AI, for those higher performing teams, the value is exponential, he said, not just in code and test generation, but in its integration within the integrated developer environment, telling them what to do.

Cornago said, “But honestly, if you look at the teams that aren’t high performing, they are not high performing because we don’t want them to be high-performing.”

Gene Kim, founder of IT Revolution which hosted both events, remarked that when you find this disparity among teams, architecture is often the discriminator: “We know that architecture, as measured by the degree to which teams can do what they need to do without communicating, coordinating, to the degree which they have independence of action.”

This indeed is the key cause of this discrepancy, Cornago confirmed, as well as sometimes the seniority of teammates, including how mature a team is on key DevOps metrics, which are linked to architecture. Specifically, he said it comes down to how the architecture was enabling the DevOps practices, including release cycle times, the number of releases, mean time to release and mean time to recover.

It’s important to emphasize the language he applied throughout both sessions. He in no way blames those teams, but rather the systems, tooling and processes his own team has put in place for them.

“It’s not the engineers’ fault,” Cornago said. “Let’s be clear, it’s our decision as a company because typically these engineers are working in parts of the code, some monolithic components of our architectures, where we decided — due to economies of scale, due to efficiencies — not to create fancy microservices to do that.”

He went on to give the example of Adidas’s omni-hub order management system, which separates all the digital experiences, including apps, ecommerce and marketing, from the physical world, which includes architectural components that are only touched once every six months or so. Systems like these don’t demand continuous deployment or microservices modernization.

“The closer you are to the ERP or the core processes of the company, the harder it gets,” Cornago said. “It’s complex because we decided to be complex.”

“We’re not planning to fire any of our ERP engineers. We’re not blaming them for the time that they spend coding,” he continued, “because it’s very clear that every time they touch something, the same line of code can affect two or three of our core processes, like financial reconciliation, inventory location, replenishment.”

This audience, on which the core business processes rely, cannot be ignored in the rush to adopt generative AI and other shiny-shiny.

“They work sometimes in closed ecosystems and different partners are in different states with regards to the adoption of GenAI,” Cornago said. “Not everyone is opening their APIs or codebases or IDEs to a natural or smooth use of GenAI.”

It’s also not relevant to focus on AI-generated code when that’s less than 15% of these engineers’ time spent. It’s much more important he said, that his team focuses on improving their environment and the organizational processes.

In the end, Cornago said, “Embracing change, and working on our ways of working is more impactful than GenAI.”

The post How Adidas Drives Engineering Success, Including With GenAI appeared first on The New Stack.