Platform Engineering was supposed to be the solution to scaling DevOps. As the graphic shows, there are dozens of talks from last year’s PlatformCon explaining how and why Platform Engineering is the only way to scale Ops teams. But if Platforms are the light at the end of the scaling tunnel, why did Accelerate’s State of DevOps report show limited gains from organizations using an internal developer platform? Why did they find an 8% decrease in throughput among those using a platform compared to those who do not?

My brilliant colleague and platform luminary, Abby Bangser, sparked a lightbulb moment for me a few weeks ago. In our discussions about building platforms, we are missing someone: the teams and experts who contribute their knowledge and expertise to platforms.

I’m talking about the database teams, who know precisely which DBs are used in the organization, the assigned billing rules, and when to use a single tenant instead of a multitenant architecture. I’m also looking at the security team, which knows which scans and standards must be applied to everything so the business doesn’t lose its compliance and accreditation status.

Here are seven talks about scaling using platform engineering or how platforms will take over the world from PlatformCons over the years. You can see all these talks and more on their YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@PlatformEngineering

The platform team becomes a bottleneck if we don’t build our platforms to collaborate with these contributors. They must become experts in those domains and translate that knowledge into something the platform users consume. In trying to centralize these functions, the platform engineers become a middle person who wasn’t there before.

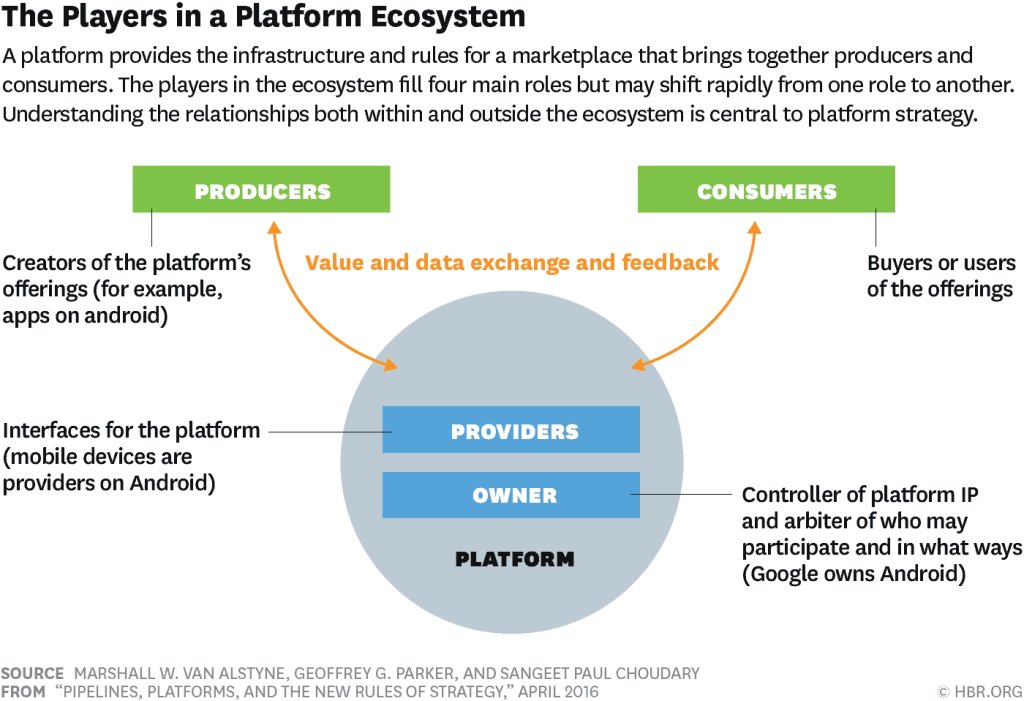

This revelation should have been evident to me. We were building Internal Developer PLATFORMS. Platform businesses figured this model out decades ago — their platforms support the consumers of value (platform users, aka developers) and value producers (for example, the Database team who want to create a DB offering on the platform). In my experience, we forget the producers.

*see refs for my loosely curated list of talks

Introduction to the Platform Business Model

The evolution of technology has shown us time and again that those who innovate

are the ones who shape the future. Alan Kay’s words resonate strongly in the modern

era, where software, artificial intelligence, and digital transformation continue

to drive change across industries.

The evolution of technology has shown us time and again that those who innovate

are the ones who shape the future. Alan Kay’s words resonate strongly in the modern

era, where software, artificial intelligence, and digital transformation continue

to drive change across industries.

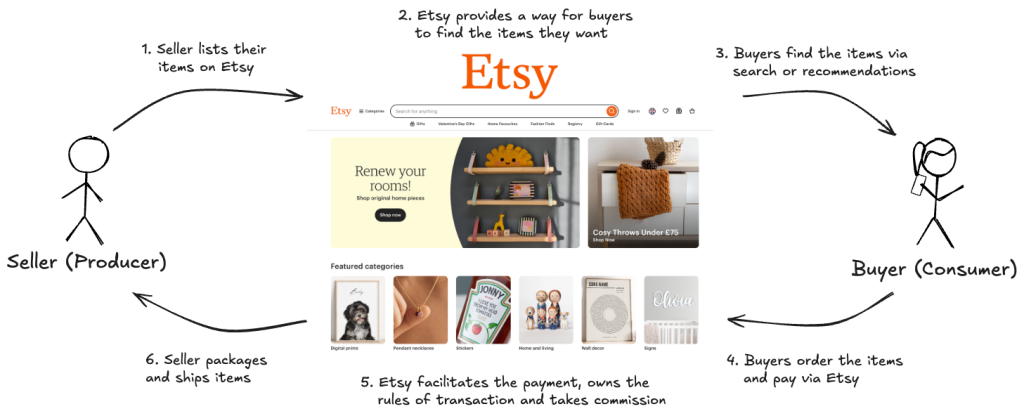

The article quoted above was the first time I had heard of “Platform Business” concepts. As opposed to traditional “pipeline” or “linear” businesses, which take raw materials and create a product that is sold to customers, “platform” businesses instead “facilitate interactions across a large number of participants.” A classic example of this is Etsy.

Etsy “bring[s] together millions of buyers and sellers in one online marketplace”. Its platform facilitates the transaction of craft goods between independent sellers and buyers. Etsy does not produce jewelry, clothes, gifts, or packages; it posts those products to buyers. Instead, Etsy provides services to manage your items as a seller and ways to find those items as a buyer. It also outlines some of the terms and agreements between sellers and buyers.

Another example is Uber — they facilitate ride-shares between drivers and passengers. It owns the algorithm to find and connect drivers and passengers, but it does not own the vehicles, nor (perhaps controversially!) does it employ the drivers. It sets out the terms between each side of the platform, optimizing both the rider’s and driver’s ability to receive value (getting the rider where they need to go and paying the driver money).

The most successful platform businesses rely on the network effect — the more valuable stuff your platform offers, the more users will be attracted to join. The more users you have consuming value, the more producers will want to add valuable stuff to your platform. The more valuable stuff your platform offers… and on and on and on.

I Learned That I Had Only Been Doing Half My Job for Years.

Nearly every one of the half-a-dozen platforms I have built suffered from the same problem. Our end users loved using the platform we were building; however, we could not get services there fast enough. This meant decommissioning old products took months (sometimes years!), teams created shadow IT to get things done, and critical business projects were delayed or blocked while waiting on our platform. None of those things felt great as the product manager for the Platform.

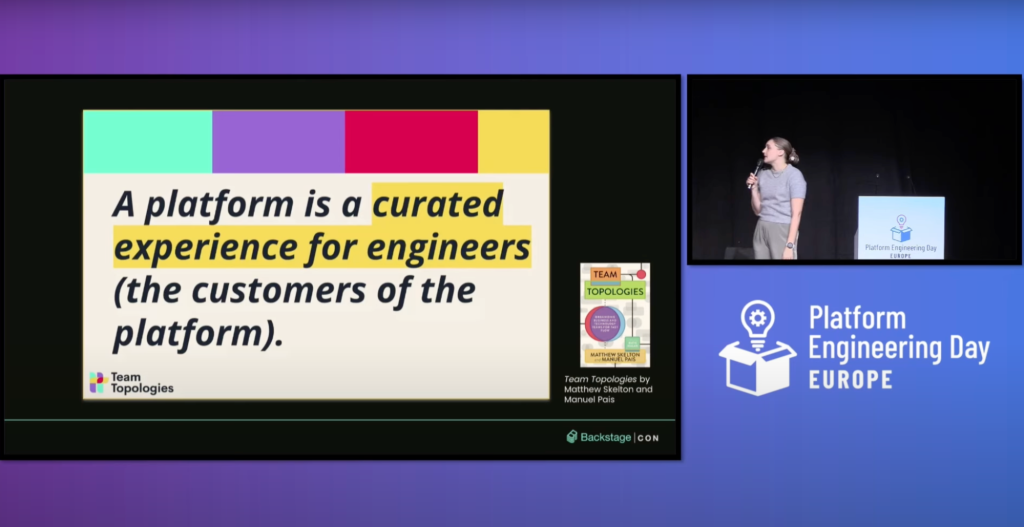

A huge part of product management is understanding your customer — the usability and value of your product. That’s true for platforms, too. Sam Coffman talks about this wonderfully in her talk “Boosting Developer Platform Teams with Product Thinking.” And she shares a quote that I have also shared with customers and in talks:

Sam Coffman at Platform Engineering Day 2024

“A Platform is a curated experience for engineers (the platform’s customers)” is a quote from the Team Topologies book. It is excellent and doesn’t contradict the platform business way of thinking, but it only calls out one side of the producer/consumer model. This is precisely the trap I fell into.

When I worked with platform builders, we focused almost entirely on the application teams that consumed platform services. We rapidly became the blocker to those teams, just like the SRE and DevOps teams that came before us. We couldn’t onboard capabilities and features fast enough, meaning we were supporting the old ways while trying to build the new.

When I worked with Abby to better understand our users, I realized that I’d been doing half my job for years. We’d taken on all the work of sourcing, curating, and producing services and functionality for the platforms we were building. By only focusing on the platform’s users and ignoring the producers, I’d cut the network effect loop in half.

Kratix’s 3 Platform Personas: Penny, Anne, and Vanessa

Customer personas are one of the best tools for making decisions about your product. ”The persona is an archetype description of an imaginary but very plausible user that personifies these traits [as a user of your product] — especially their behaviors, attitudes, and goals.” – Marty Cagan, SVPG. Personas are nothing new and are still essential in the Product Management tool kit.

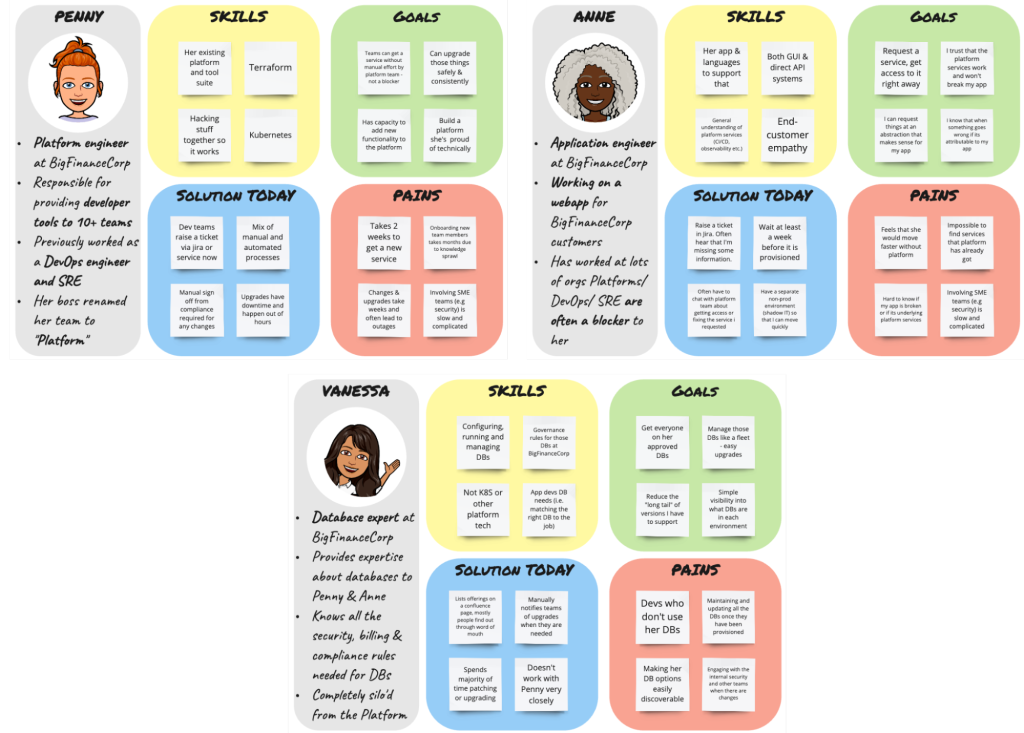

When I joined Syntasso (the creators of Kratix), I was introduced to our three personas: Penny, the platform engineer; Anne, the application developer (consumer of platform value); and Vanessa, the Vendor (producer of platform value). From the beginning, we were thinking about how to make it just as easy to contribute to the platform as to consume from it. This allows teams using Kratix to capitalize on the network effect fully.

Everything we build supports one of these personas’ goals, making prioritizing work a more transparent process. Penny is our product’s primary user. If we don’t enable Penny to make it easy for the teams requesting platform capabilities or those adding things to the platform, their platform won’t be successful.

This isn’t to say that you should balance your work to support producers and consumers evenly. It often makes sense to dive deeply into the experience of one of your personas for an extended period if you see an opportunity, want to focus on one area of growth, or need to improve the experience of one user group. The real problems arise when you forget one and describe it unintentionally.

| Penny (Platform Engineer) | Anne (App Dev/Consumer) | Vanessa (Vendor/Producer) |

|---|---|---|

| • Resource health checks • Pipeline permissions |

• Internal Dev Portal (Backstage.io) integrations • Resource health checks |

• Promise writing CLI • Terraform integration • Pipeline permissions |

*Some of these features are only supported in our enterprise offering, Syntasso Kratix Enterprise (SKE). Learn more about SKE here.

Here’s part of the 2024 Kratix roadmap. To illustrate my point, I’ve separated the features by persona. Not only did we choose to do a little bit to support all of our key users, but some of the features also benefit multiple personas (which has the added benefit of splitting the feature into smaller slices by focusing on one persona at a time!)

Notice how much of our work focuses on the Vanessa experience. Making it easy to contribute to your own and other people’s platforms is a core part of our strategy — because it is what CTOs and CIOs are desperate for.

Embracing Multiplayer Mode

Chris Plank, Enterprise Architect at NatWest, discusses this in our interview for his Platform Engineering Day talk: “We have since been set four challenges by leadership that I talk about: do things faster, do things simpler, enable inner sourcing, and deliver centralized capabilities in a self-service way… Our inner sourcing model will allow us to have multiple teams working on our platform… They are empowered to start contributing changes.”

And he’s not the only one. Many of our customers come to us needing a framework for inner sourcing, multiplayer mode, or internal marketplaces. Each of these things is different, but they all point to the pain CIOs and CTOs feel today: an inability to scale specialists (i.e., Kratix’s Vanessa persona) and get the maximum value from their internal developer platforms.

Having a persona to represent the person contributing to your platform (by whatever mechanism works for your organization) forces you to consider this experience. Neglecting them becomes glaringly obvious — especially if you occasionally map your recently delivered features to your personas!

This blog is too long, so if you want to learn more about the multiplayer mode, Paula Kennedy, COO at Syntasso, provided an excellent overview in her Platform Con talks, “Switch your internal Platform to Multiplayer Mode.”

Wrapping up: Don’t Forget About Platform Producers

By having a platform, you have already taken the first step towards fostering this collaboration by providing a single place and consistent experience for application teams. If, as I did, you find your platform team overwhelmed and overloaded, you may find that focusing on your producer persona for a bit means you get loads more platform capabilities, and your customers are super happy.

The post The Missing Piece in Platform Engineering: Recognizing Producers appeared first on The New Stack.