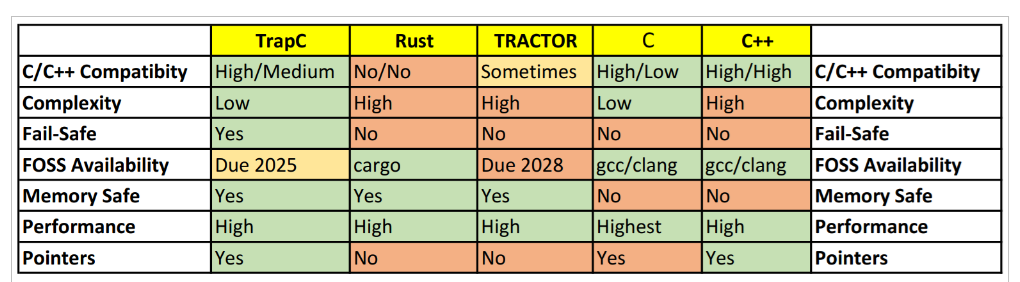

From Rowe’s paper.

Two weeks ago, the C programming language’s international standardization working group heard entrepreneur Robin Rowe‘s proposal for TrapC, a ground-breaking memory-safe extension of the C programming language.

“After my presentation, I was told I should have asked for more time,” Rowe said in an email interview to TNS, “that 30 minutes wasn’t enough. So yes, good interest.”

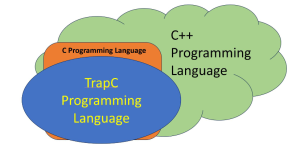

Rowe’s extension would be “highly compatible” with existing C code, and even “somewhat compatible” with C++, offering another way forward for the world’s massive codebase of existing memory-unsafe code.

The ultimate goal, according to the whitepaper Rowe presented, is “to enable recompiling legacy C code into executables that are safe by design and secure by default” with very little code refactoring.

Both the C and C++ programming languages have been under scrutiny in the past few years for allowing developers to inadvertently write programs with memory errors, faulty code that allows malicious users to overwrite memory block with their own nefarious code. TrapC could put an end to this whole class of errors.

How TrapC Is Designed

To make it all happen, Rowe is heading up Fountain Adobe, a non-profit research institute near Washington D.C. It was founded in November “for maintaining the TrapC language specification and for releasing the free open source TrapC compiler,” and Rowe told me that the non-profit is “funded for the rest of the year,” though corporations are welcome to sponsor continuing development.

There’s already a compiler that produces x86, x64 or ARM executables from standard C code, Rowe confirmed in his email, and they’ve now working on also supporting additional language extensions for TrapC. (They’re adding the keyword trap to offer safe-by-default error handling and alias for easy operator and type overloading, while reusing C++ code-safety features like constructors, destructors, new, and member functions.)

TrapC does remove two C keywords: goto and union, which it describes as “unsafe and having been widely deprecated from use.” (Later the white paper recommends C code using those keywords could be kept in a library of C code and then linked to by a TrapC project…) But there’s building excitement about the upcoming language’s promise and potential…

“C and C++ programmers may not need to learn Rust after all to participate in the push for memory safety,” wrote the Register.

Safety With Performance

TrapC “is on track to release in 2025,” Rowe told me Saturday. And he promised that “When there’s enough to demo, we will put it live online — so anyone may try TrapC.”

It’s an ambitious project. Rowe has described TrapC’s goal as no less than “to make C/C++ software unhackable at the language level, to compile software that cannot be exploited by unexpected behavior and will never crash.”

But there’s specific techniques in place to make it happen.

“When C code is compiled using a TrapC compiler, all pointers become Memory Safe Pointers and are checked,” Rowe told the ISO C standards body meeting, according to the Register. In TrapC the compiler determines which pointers can go out of bounds — and will set them to zero.

One result of this, according to the white paper, is that TrapC pointers “always point to valid memory” and “cannot overrun or contain garbage.” Since TrapC knows (and watches) the buffer size, it knows when erroneous code “would be trying to touch invalid memory past the null terminator.”

But could this also bring performance improvements? “Unlike a C compiler, the TrapC compiler has perfect information about the regions of memory its pointers hold,” Rowe tells me — meaning it can optimize better. Rather than checking each and every pointer access, one-by-one, “The TrapC compiler can avoid most memory-safe-pointer boundary checks by using AI code reasoning.”

This leads him to a provocative assertion. “Experts expect memory safety to be expensive,” Rowe tells me, “but is that necessarily true?” In the end TrapC’s compile code could be both smaller and faster, Rowe tells me — meaning that when calculating performance costs, TrapC memory safety “may be better than free…”

Performance enhancements may also come from other TrapC language features. For example, some programming languages have a try keyword that throw an error if the attempt is unsuccessful, leading to a code branch for that exception. But the white paper notes that “With TrapC, quoting Yoda from Star Wars, ‘There is no try, only do or do not’.”

Returning from an error-free function call just skips over the error-handling trap code block. The paper acknowledges this is a new syntax that’s not found in C or C++.

So unlike C, TrapC responds to a buffer overrun (and other errors) by terminating with a useful error message.

And while this sounds like a minor change, Rowe tells me that the TrapC “trap” error-handling mechanism “is better in time and space than any existing error handling mechanism available in C or with C++ exceptions.”

More Safety Improvements

Rowe’s white paper includes the example of code which would ordinarily cause a buffer overrun error, but in TrapC instead terminates the program “with a useful error message.”

But the same will be true for any other unanticipated error condition, the paper adds (including, for example, divide-by-zero errors) — unless the programmer explicitly creates their own trapping error handler.

The white paper also points out several other TrapC safety features:

- To avoid common errors, TrapC offers the automatic memory management found in many modern languages.

- While C can also trigger a buffer overrun by appending to a string, “TrapC strings expand”.

- TypeC offers automatic type-checking in printf statements when the specifier “{}” is used, i.e.

printf("{}",var);. - “TrapC printf() and scanf() are typesafe, overloadable, and have JSON and localization support built in.”

- TrapC also has “wrapper” functions for other standard C POSIX library functions.

- The C programming language includes a free() keyword for deallocating memory — creating a possible error if a pointer then accesses that location. But since TrapC’s memory management happens automatically, that’s never an issue, the paper explains. So “for C compatibility, it is ok to call free() in TrapC, but it is ignored.”

- TrapC “has an integer-based ‘decimal’ fixed-point data type suitable for use in financial transactions”

- The white paper adds that in the future TrapC might even try to add thread safety features to help prevent race conditions.

In short, TrapC “is a programming language forked from C, with changes to make it LangSec and Memory Safe,” the paper concludes. “To accomplish that, TrapC seeks to eliminate all Undefined Behavior in the C programming language…”

An AI-Powered IDE?

In March of 2024, Rowe also founded a for-profit startup called TRASEC, which is working on generative AI programming technology.

“Funding so far is friends and family,” Rowe told TNS, adding that he’s “Chatting with VCs.”

TRASEC is helping develop the TrapC compiler, but that’s just the beginning. The whitepaper says the startup also hopes to ultimately release a special trapc cybersecurity compiler with AI code reasoning — and to do it sometime in 2025.

As Rowe told the Register, “The business plan is to give the compiler away as free open source and to have an AI IDE that’s our paid product.”

His ultimate goal is “to have AI create software that is unhackable and uncrashable,” Rowe said in January while answering questions in Reddit’s “Entrepreneurs” subreddit.

“Out in the world, generative AI is making great strides writing Python code,” Rowe tells me, but it’s still “not so good” at writing C code. But what if AI-generated code was so well-organized it provided full-fledged support for “modular” programming, with all of an application’s individual functionalities neatly tucked away into separate files. There could even be auto-generated unit tests, Rowe suggests: “modular code with unit tests, not spaghetti code.”

So unlike C, TrapC responds to a buffer overrun (and other errors) by terminating with a useful error message.

He’s working on that too. Rowe’s whitepaper points out that C currently doesn’t have a standardized build system as part of the language itself (like Rust’s Cargo toolchain). So looking ahead, “It is vital to TrapC to have a portable, easy to use, toolchain like Rust, so programmers may quickly and easily create build systems that work across operating systems.”

Fortunately, Rowe already has a toolchain for generating cmake build files that he’d created for his long-running (and open source) graphics software project CinePaint. Rowe led the open source fork of the GNU Image Manipulation Program (or GIMP), and tells me that “The GIMP maintainers gave as their reason for abandoning the Hollywood branch of GIMP, later renamed CinePaint, as because it was so buggy. It’s fair to say the difficulty removing memory bugs in CinePaint, written in C, gave me the experience and motivation to create TrapC.”

And it’s also left him with a custom-built toolchain that not only generates the code for cmake files, but also boilerplate code for classes, application code, and even unit tests. (And Rowe’s paper points out it can even be used “retroactively for existing projects that may lack a build system.”)

“Cmaker supports C++ currently,” according to the paper, but “Support for C and TrapC is coming.”

Compatibility and Performance

One slide in Rowe’s presentation acknowledged TrapC “retains” the minimalism of C — meaning it doesn’t offer the C++ version of templates, exceptions, function overloading, inheritance, or polymorphism.

“C compatibility and high performance is what C programmers tell me is absolutely required of a memory safe language to be an acceptable replacement,” Rowe explained in our email interview. “Foregoing memory safety in C was a design compromise made in the 1970s. It was a tough design choice between performance, ubiquity and safety — pick two. My TrapC mission is to pick all three.

“Be highly compatible with C and have memory safety that costs nothing compared to manual memory management in C.”

Whatever its shortcomings, one final slide in Rowe’s presentation states unequivocally that TrapC “secures C/C++ pointers, scanf, printf, and malloc.”

And it includes what seems like a mission statement for TrapC. “Harden legacy code: compile ordinary C/C++ code into programs that cannot buffer overrun, cannot crash.”

The post Memory-Safe C: TrapC’s Pitch to the C ISO Working Group appeared first on The New Stack.