If you’re part of a dev team overlapping with any kind AI initiative right now, you’re probably finding yourself pushed toward expensive, proprietary vector databases. The reasoning might seem sound: Dedicated solutions for vector search must be better than general-purpose databases. But this assumption is leading teams into costly vendor lock-in situations, who then realize they’re paying premium prices for capabilities they could get from open source alternatives.

Several open source databases — ones that dev teams can adopt without massive startup costs or painful lock-in periods — are already excellent at vector search. While Apache Cassandra 5.0, PostgreSQL and OpenSearch are all solid options, one emerging alternative is particularly worth developers’ attention right now: ClickHouse, an open source database that combines high-performance analytics with some downright impressive vector search capabilities.

ClickHouse is built from the ground up for online analytical processing (OLAP) of large data sets. This foundation turns out to be perfect for vector search operations, especially at scale. While most vector databases force teams to build separate infrastructures for search and analytics, ClickHouse handles both seamlessly, making it even more valuable as AI workloads grow more complex.

Why ClickHouse Stands Out for Vector Search

ClickHouse’s columnar storage architecture, originally designed for analytical workloads, is also great for vector operations. It delivers the performance needed for real-time similarity searches across massive data sets. The distributed architecture scales horizontally, letting you spread workloads across CPU cores and disks without the complexity typically associated with distributed vector databases.

But its integration story makes ClickHouse particularly appealing, in my opinion. It slots right into existing data pipelines with native support for Apache Kafka and Spark, while also playing nicely with AI tools like Hugging Face and LangChain. And unlike proprietary solutions, you can dive straight into vector operations without additional infrastructure or licensing. It’s all supported right out of the box on the same high-performance architecture.

Building a Wikipedia Search Engine With ClickHouse

Before diving into the code, let’s cut through the jargon: Vector search works by turning content (like text, images or audio) into lists of numbers called embeddings. Think of these as coordinates that map out how similar different pieces of content are to each other. When you’re building AI applications — especially ones that need to understand context or find relevant information in real time — these embeddings are your secret weapon.

Let’s see how this works in practice by building something useful: a search engine that can answer questions using Wikipedia articles as its knowledge base.

Quick Setup: Jumpstarting With Pre-Built Embeddings

While you can generate your own embeddings using Hugging Face or LangChain (and I recommend this approach for production), I’ll fast-track our example using a pre-built data set. The Hugging Face community has already created embeddings for millions of Wikipedia articles, which they’ve made freely available. This lets us focus on the core task: setting up ClickHouse for vector search.

I’ll use a data set that includes Wikipedia text, embedding vectors and metadata values. The embeddings are 768-dimensional vectors (essentially long lists of numbers that represent the content of each article). Let’s walk through how to load this data and start running searches.

From Data Set to Working Search Engine: A Step-by-Step Guide

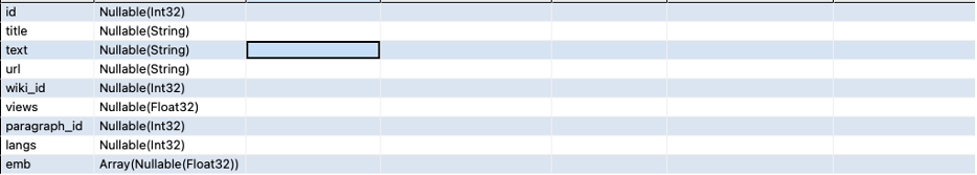

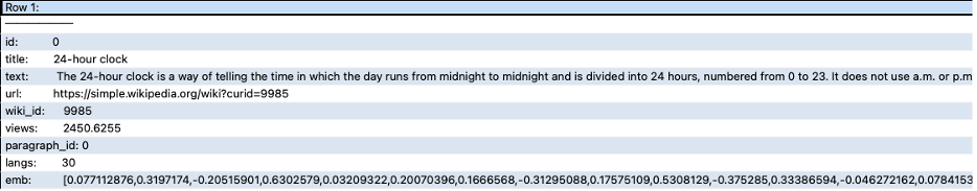

First, let’s inspect what we’re working with. The dataset has a few key columns:

emb: the embedding vectors (arrays of 768 floats representing each article)text: the actual Wikipedia article contenttitle: article titles- Additional metadata like view counts and language info

I’ll use two commands to explore this data in ClickHouse:

DESCRIBE: to understand the column structureSELECT: to peek at the actual content

Here’s the code to inspect our dataset:

-- Describes the content of the parquet file

DESCRIBE

url('https://huggingface.co/datasets/Cohere/wikipedia-22-12-simple

embeddings/resolve/refs%2Fconvert%2Fparquet/default/train/0000.parquet',

'Parquet')

SETTINGS enable_url_encoding = 0, max_http_get_redirects = 1;

-- Select lines to get the data in the parquet files

SELECT *

FROM

url('https://huggingface.co/datasets/Cohere/wikipedia-22-12-simple

embeddings/resolve/refs%2Fconvert%2Fparquet/default/train/0000.parquet',

'Parquet')

LIMIT 2

FORMAT Vertical

SETTINGS enable_url_encoding = 0, max_http_get_redirects = 1;

A note on settings: I set enable_url_encoding = 0 since the URL is already encoded, and max_http_get_redirects = 1 to allow one redirect hop when fetching the file.

Running these commands yields:

Creating Our Vector Search Table

Now that we understand our data structure, I’ll create a table to store it. I’ll use ClickHouse’s MergeTree engine, which is optimized for analytical workloads like vector search:

CREATE TABLE wiki_emb

(

id UInt32,

title String,

text String,

url String,

wiki_id UInt32,

views UInt32,

paragraph_id UInt32,

langs UInt32,

emb Array(Float32)

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY id;

Note: I’m using the id column as a simple index for now. I’ll cover performance optimizations later.

Loading the Wikipedia Data Set

Now I’ll populate the table with data from multiple Parquet files. A few quick settings first:

SET max_http_get_redirects = 1

SET enable_url_encoding = 0

INSERT INTO wiki_emb

SELECT *

FROM (

SELECT * FROM url('https://huggingface.co/datasets/Cohere/wikipedia-22-12

simple-embeddings/resolve/refs%2Fconvert%2Fparquet/default/train/0000.parquet',

'Parquet')

UNION ALL

SELECT * FROM url('https://huggingface.co/datasets/Cohere/wikipedia-22-12

simple-embeddings/resolve/refs%2Fconvert%2Fparquet/default/train/0001.parquet',

'Parquet')

UNION ALL

SELECT * FROM url('https://huggingface.co/datasets/Cohere/wikipedia-22-12

simple-embeddings/resolve/refs%2Fconvert%2Fparquet/default/train/0002.parquet',

'Parquet')

UNION ALL

SELECT * FROM url('https://huggingface.co/datasets/Cohere/wikipedia-22-12

simple-embeddings/resolve/refs%2Fconvert%2Fparquet/default/train/0003.parquet',

'Parquet')

) AS data_sources;

Optimizing Performance

Before starting to run searches, a few optimizations:

1. First, I’ll compress the embedding vectors using ZSTD, which works well with floating-point numbers:

ALTER TABLE wiki_emb MODIFY COLUMN emb Array(Float32) CODEC(ZSTD);

Note that while traditional compression methods like LZ4 don’t really work well with embeddings, ZSTD can significantly reduce storage without affecting performance.

2. For better insert performance, always use batch inserts to reduce overhead, considering a file_name column to track data sources, and look into quantization if you need to reduce storage further.

Running Similar Vectors

Now comes the fun part — actually finding similar content. I’ll break this into two steps, starting with using Python to convert the search query into a vector:

# Install the Cohere Python SDK

# pip install cohere

import cohere

# Initialize the Cohere client with your API key

api_key = 'your-api-key-here'

co = cohere.Client(api_key)

# Define the text you want to generate embeddings for

text = " Who created Unix " # Replace with your query

# Generate the embeddings using the multilingual-22-12 model

response = co.embed(

texts=[text],

model='multilingual-22-12'

)

# Extract the embedding from the response

embedding = response.embeddings[0]

# Print the embedding

print(embedding)

# Verify the length of the embedding

print(f'Length of embedding: {len(embedding)}')

Output:

[0.12451172, 0.20385742, -0.22717285, 0.39697266, -0.04095459

…

0.42578125, 0.23034668, 0.39160156, 0.116760254, 0.046661377, 0.1430664]

Length of embedding: 768

Note that in production, you’d typically use LangChain or a similar framework to handle embedding generation. I’m showing the basic approach here for clarity.

Finding Similar Articles

Once we have our query embedding, we can use ClickHouse’s built-in vector similarity functions to find the most relevant Wikipedia articles:

SELECT

title,

url,

paragraph_id,

text,

cosineDistance(emb, [Paste the embeddings]) AS distance

FROM wiki_emb

ORDER BY distance ASC

LIMIT 5

FORMAT Vertical;

This uses cosineDistance, but ClickHouse also supports other similarity measures like L2Distance if those better suit your needs.

The query ranks articles by how similar they are to our search term “Who created Unix” with lower-distance scores indicating better matches.

Real-World Performance

Running this setup on modest hardware (8 GB RAM, 4 CPUs), we got impressive results:

- Query time: 0.633 seconds

- Data set size: 485,859 rows

- No special tuning or optimization

What makes this particularly compelling is the way ClickHouse handles scale. Performance scales sub-linearly with data size, meaning you won’t see query times spike as your data set grows. Plus, since it’s all open source, you maintain full control over your data and infrastructure. For teams already working with large-scale analytical workloads, ClickHouse offers a pragmatic alternative to specialized vector databases without vendor lock-in.

The post Vector Search Without the Lock-In: Why Devs Like ClickHouse appeared first on The New Stack.