As applications run in production, you’ll need to find out what’s happening. You might want to know if you’re overloading the hardware, moving to the wrong feature in an A/B test or, on the mobile side, even such simple contingencies as whether the battery is running out.

Developing an app to send information about itself means adding instrumentation. Apps can send such telemetry as metrics, logs and traces to allow teams to interpret the internal state of the application. This concept is the basis of collection in observability.

Standardizing the collection and format of these signals is in large part the goal of the OpenTelemetry (OTel) project. An added benefit is, if most applications in a given language need to observe the same types of operations and workflows, developers building on the OTel standard can identify and build auto-instrumentation to do the work for them.

The Joys of Auto-Instrumentation

It certainly would be nice if you could learn everything you need to know about an application without doing any additional work. For example, imagine you could learn which services in your highly customized build were running out of resources. Or perhaps you saw network requests repeatedly fail at a key part of an app’s flow.

Mobile apps run on specific devices and operating systems, which means that certain operations are standard across every app instance. For example, in an iOS app built on UIKit, the didFinishLaunchingWithOptions method informs the app developer that a freshly launched app is almost ready to run. Listening for this method in any app would in turn let you observe and learn more about the completion of app launch automatically.

Quick, out-of-the-box instrumentation like this is easy to use. By importing an auto-instrumentation library to your app, you can hook into the activity of your application without writing custom code.

Using auto-instrumentation provides standardized signals for actions that should be recognized in a prescribed way. You could listen for app launch, as described above, but also for the loading of views, for the beginning and ends of network requests, crashes and so on. Observability would be great if imported libraries did all the work.

Mobile App Workflows and What You Can Control

However, making sense of your mobile app requires more than just monitoring the ubiquitous signals of mobile app development. For one, mobile telemetry collection and transmission can be limited by the operating system that the app user chooses, which is not designed to transmit every signal of its own. Additionally, third-party libraries for common use cases like networking and UI rendering are usually closed source and not designed with auto-instrumentation in mind.

Finally, and most importantly, the specific flows of the app come from the intent of the app developer, in a way only they can provide instrumentation for. In other words, the way an app is built is entirely customized to the intended use of a user. That’s the point of building a new app.

For example, navigating screens with ongoing network requests and caching occurring across threads is a common set of simultaneous activities. Auto-instrumentation might capture navigation and networking as separate signals occurring during the app’s life cycle. Making sense of these activities together in the same user flow, or even making sense of when they happened in a user’s journey, requires input from the app developer.

Manual Instrumentation, With a User in Mind

A key difference between mobile instrumentation and that of backend systems is the user. Backend flows are built to follow an imperative, “if this happens, do that” framework in response to operations. Not so with mobile apps. The user is touching a screen, scrolling and tapping buttons in their preferred order, rather than a predetermined routine for services and programs.

As a starting point, mobile instrumentation needs to tie together events within the user’s grasp in their specific context. This isn’t necessarily the intraservice context that observability engineers are familiar with. Instead, it’s much more human: The instrumentation needs to reflect the user’s journey within a session, or one use of the app.

Take, for example, completing a checkout flow in an e-commerce app. Navigating from screen to screen requires network requests for cart availability, payment information and purchase attempts, as well as the passing of this information between screens. The correct ordering of these screens is obviously important, as no developer should build a checkout flow that starts with a purchase request.

There might be additional factors that need to be accounted for in this session, occurring outside the flow. The user’s location might restrict certain types of purchases in a specific country. You’ll want to know if shoddy Wi-Fi stopped the flow halfway through. Even with the best user experience in the world, the app’s software itself is operated by someone else, so capturing the details of their experience is the best way to make sense of it.

Instrumentation Mingling

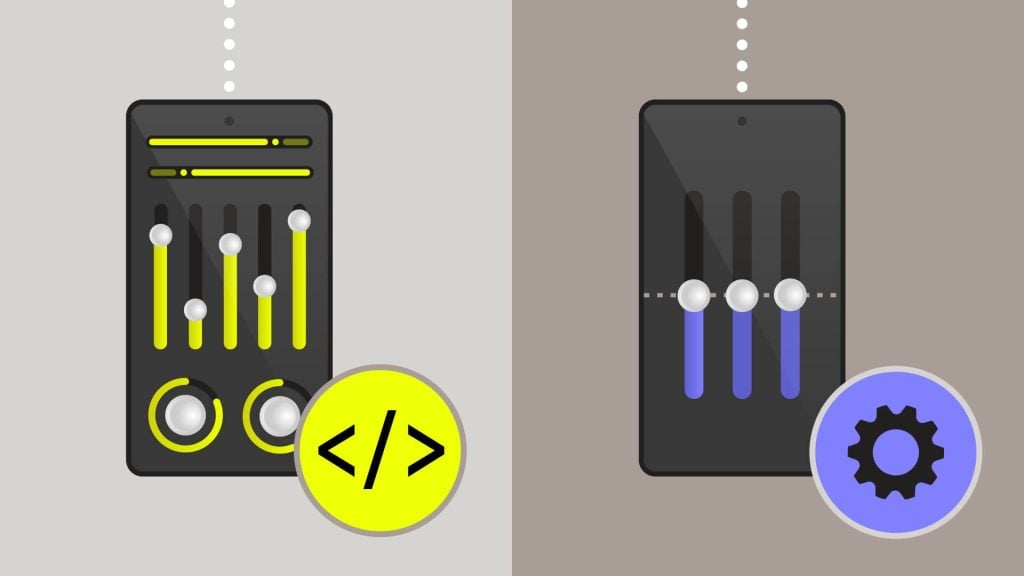

Some signals can be captured automatically in apps and are ubiquitous, while others take manual instrumentation to get into the specifics of their intention. Putting them together would potentially be the best goal, as having all signals together with the correct contextual information would give the broadest picture of app activity.

While manually tracing navigation, you could use your automatic networking instrumentation to see that the wrong network request fired. You could then work backward to make sense of the user activity that led to this incorrect activity.

More broadly, for any workflow, there might be custom data you want to add that allows you to track subworkflows that are bespoke to your app. The SDK that produces auto-instrumentation needs to provide this facility, to allow custom and automatically captured data to “mingle.”

Finding the Right Tools

In the end, apps will need their instrumentation to come through a blend of manual and automatic instrumentation. Ideally, mobile apps should rely on auto-instrumentation to capture common workflows and manual instrumentation to capture custom workflows, but they should also enhance auto-instrumented telemetry so that custom context can be mixed in with what is automatically captured.

How easy it is to add manual instrumentation will depend on the API exposed by the SDK you’re using. This is why SDKs like Embrace’s Android and Apple SDKs exist: to provide out-of-the-box instrumentation for platforms and common library-specific workflows that most mobile apps would want. Embrace’s SDKs are tailored to build mobile context into observability, so mobile devs don’t have to face the same challenges over and over.

At Embrace, we’re looking to grow the capabilities of the information that is captured on mobile, to make it easy to know exactly what affects the user experience. Join our community Slack to ask questions and find out more about how to use mobile observability built on OpenTelemetry.

The post Choosing Manual or Auto-Instrumentation for Mobile Observability appeared first on The New Stack.